by Robert Miller

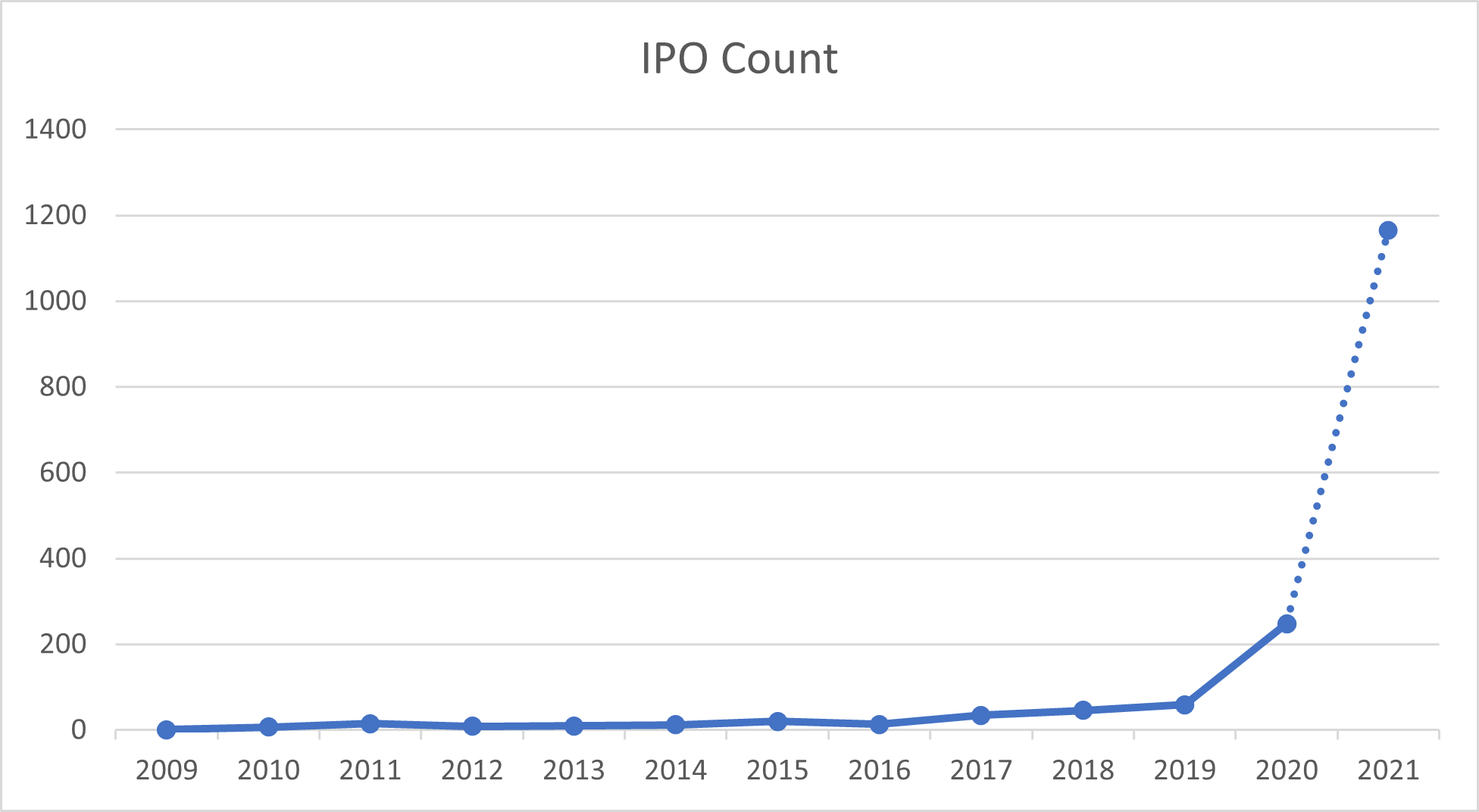

Special-purpose acquisition companies, otherwise known as SPACs, are the current hype and frenzy on Wall Street. Amidst a global pandemic, SPACs had a phenomenal year in 2020 with 248 initial public offerings (IPOs) raising on average US$334m, compared to 59 in 2019 raising on average US$230m (1). Notable SPAC IPOs in 2020 include Richard Branson’s US$400m IPO to expand his Virgin empire, and hedge fund billionaire Bill Ackman raising US$4bn. Not only are SPACs raising record levels of capital, but new listings also recorded an average rise of 6.5% on their debuts (from 2003 to 2020, the average first-day return of SPAC IPOs was 1.1%) (2).

As of 8th February 2021, there have already been 124 SPAC IPOs. That is close to half the amount of all the SPAC IPOs in 2020. If the current trajectory of SPAC IPOs continues, there will be in excess of 1,000 in 2021.

A SPAC, or “blank cheque” company is a public entity with no established commercial activities. A SPAC has the strict intention of entering public markets and raising funds from investors through a public offering, which usually raises capital at the standard rate of $10 per share. The management team of a SPAC, known as the sponsors, will then seek to find a merger partner, or a “target”, typically a private company looking to go public that can generate interest among investors.

The target company then takes the SPAC’s place on the exchange, allowing investors to transition from holding shares in the SPAC to holding shares in the target company. Typically, a SPAC will have two years to secure a target or the SPAC sponsors must return the capital they’ve raised back to the investors who provided the initial capital.

A SPAC does not need to purchase a controlling stake in the target company. A SPAC can simply become a shareholder in the target company. SPACs have the flexibility to raise additional capital & debt funding, hence the target company may be much larger than simply the amount of cash the SPAC holds.

There is no question that SPACs are currently in favour with market participants. Given the current momentum and media hype, particularly with high profile celebrities such as NBA icon Shaquille O’Neal endorsing their own SPACs, one could think that SPACs are a new investment vehicle. This is not the case as SPACs have been around for decades. They were previously known as “blind pools” and carried a shady reputation as they were linked to penny-stock frauds on Wall Street.

New laws and regulations have helped bolster their reputation. These regulations include the following safeguards:

Instead of an IPO candidate raising capital to go public on an exchange, in a SPAC structure investors pool their money together first, and the operating company comes later, reversing the traditional IPO process. Due to their structure, which offers a quicker and cheaper route for companies wishing to list on a public exchange, SPACs are becoming a credible source of financing for private companies looking to go public.

SPACs claim they serve a useful purpose by teasing out companies that might not otherwise list due to the costly & length process of a traditional IPO. For investors, the ability to gain access to companies that may otherwise not have been possible is great to see.

SPACs have been criticised for lacking transparency and providing greater returns for the SPAC management team (sponsors) rather than for shareholders. Sponsors are paid in the form of a “promote” which usually involves taking ownership of ~20% of the SPACs entity for a nominal purchase price. That stake converts into a smaller slice of equity in the new company when the SPAC executes a merger, which can lead to a huge pay off if the target company vending into the SPAC sees strong share price appreciation.

The promote is seen as a payment to the sponsor for all their efforts in finding a target company and executing the merger, all negotiated behind closed doors. The sponsor will also appoint the key management personnel to run the company once the target company has been merged.

With the explosion in the number of SPAC IPOs taking place, perhaps we may see that the promote payment amount will decrease, as private companies have a greater choice of SPACs available. Perhaps they will be able to negotiate better deals for themselves & their private company shareholders.

When a SPAC identifies a target opportunity, investors may wish to cash out prior to the investment occurring. For the remaining shareholders in the SPAC, if the sponsor is unable to attract new investors to inject capital as a direct replacement, then the cash proceeds of the SPAC are paid out to investors leaving, hence the ability to complete the transaction can be marginalised.

Whilst it is rare for SPAC deals to fail to transact within the required two-year timeframe, is this due to the impressive fees earnt by sponsors for completing the transactions or because of the quantum of private company opportunities available? If the growth in SPACs continues, competition for target companies will increase, meaning the target quality may diminish. Investors should think about this two-year time horizon trade-off with increasing scepticism.

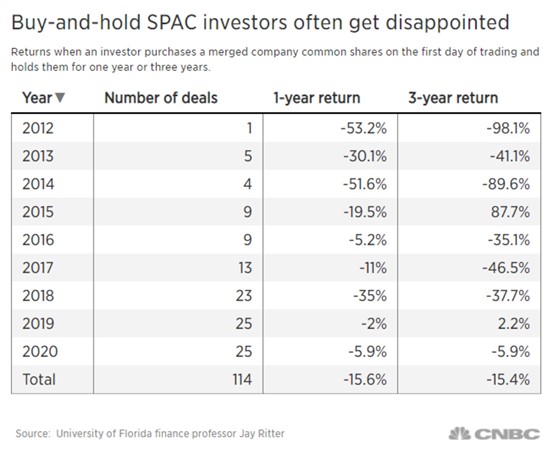

Ultimately SPACs investors do not know what the target company will be. Investors are putting their trust in the reputation, track record, and expertise of the SPACs sponsors, as well as their ability to identify and merge successful companies. Therefore, investing in a SPAC is an exercise in speculation, albeit with some downside protection. It is worth noting that the buy-and-hold investors who invest after a deal is struck often lose money. According to Jay Ritter, for the 114 companies that went public via SPAC mergers in the past 10 years, investors lost 15.6% on average if they bought a merged company’s common shares on the first day of trading and held them for a year.

As noted earlier, 2021 has seen the SPAC IPO market increase exponentially. Investors and private companies are becoming more comfortable with the model, with many retail investors embracing more speculative and volatile stocks.

In an environment where interest rates are at record lows and will be for the foreseeable future, investors are being forced to take on more risk to generate returns. Couple this with the rise of the retail investor, this surge in demand is somewhat understandable.

This environment translates well to Australia. The IPO market continues to be buoyant but we believe there are increasingly more signs of speculative activity on the ASX. At NAOS, the more IPOs we see, the more cautious we become. Knowing when the IPO tap will turn off is impossible to predict, however, regardless of the level of speculative activity in the market, record low-interest rates should continue to see solid dividend-paying companies as an attractive alternative for investors looking for income.

Investors should carefully consider the associated risks before considering SPACs or any other investment vehicle. Are SPACs a bubble or is this sustainable over the long term? Perhaps we will find out in two years’ time…

Join our investment community. Be the first to receive NAOS News, Insights and Invitations.